Magnetic Pull on the Heart,

Draws you unto Me,

Without a Compass.

Magnetic Pull on the Heart,

Draws you unto Me,

Without a Compass.

https://ciel.utsc.utoronto.ca/ojibwe-textbook/lesson/1?dialect=southwestern

Source: Ethnologue

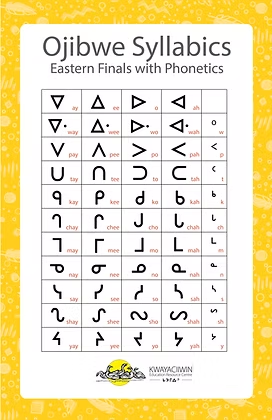

In about 1830 James Evans, a Wesleyan missionary, devised a way to write the Ojibwe language of Rice Lake with the Latin alphabet. His goal was to produce a dictionary of Ojibwe to help him to learn the language better, and to help him teach English to the Ojibwe people.

In about 1840, while working at Norway House in Hudson’s Bay, Evans invented a syllabic script for the Ojibwe language, based partly on Pitman shorthand, which had been published in 1837. It is thought that his idea to create a syllabic script was based on the Cherokee script.

Evans’ syllabary for Ojibwe consisted of just nine symbols, each of which could be written in four different orientations to indicate different vowels. This was sufficient to write Ojibwe. Evans translated parts of the Bible and other religious works into Ojibwe, and later Cree, and printed them using type carved from wood, or made from melted-down linings of tea chests.

Evans later adapted it to write Cree. The script proved popular with Ojibwe and Cree speakers, and within about 10 years, many of them had learnt to read and write it, learning mainly from family or friends. As paper was scarce at the time, they wrote on birch bark with soot from burnt sticks, or carved messages in wood, and nicknamed James Evans ‘The man who made birch bark talk’.

The Ojibwe script continued to be widely used until the 1950s and 1960s, when the integration policies of Department of Indian and Northern Affairs led to a decline in use to the script among Ojibwe children taught to write in the Roman alphabet.

Main source: Murdoch, John Stewart, Syllabics: A Successful Educational Innovation (University of Manitoba, 1981).

Ojibwe is a language of verbs. Most of the information in a sentence is carried by verbs, and verbs also tend to carry out functions that are covered by other parts of speech in other languages. For example, Nimbakade – I am hungry. This is a verb. Ojibwe doesn’t really have adjectives. To express that someone or something is in a given state or has a certain property, you almost always use a verb.

Traditional analysis of the grammar of Ojibwe (and related languages) suggests that there are four major categories of verbs in the language. Each category has its own set of prefixes and suffixes. It adds up to a lot to memorize, but don’t worry, we will take you through it step by step, one lesson at a time.

To understand the four categories, it helps to know that Ojibwe nouns come in two kinds, or “genders.” These genders are not male and female as you might be familiar with in certain European languages, but rather animate and inanimate. Animate generally refers to living things and people, while inanimate refers to non-living objects. However, there are many exceptions. For example, in many dialects, the word for rock is animate. Some speakers of the language attribute spiritual significance to this, and some don’t. In this course, we won’t get too much into the philosophy, but we will teach this simply as a property of the language. It is similar to how in Spanish “table” is feminine but “book” is masculine. As you learn Ojibwe nouns, you will have to memorize whether they are animate or inanimate. As you’ll see, this distinction also affects what verbs you can use with different nouns. We’ll talk much more about this in time.

These pronouns are fairly equivalent to their English translations, but they actually aren’t used that much in Ojibwe in ordinary conversation. This is because verbs take prefixes to indicate 1st 2nd and 3rd person, so you don’t need to add a pronoun on top of that. Here are the verb forms with prefixes:

| bare pronoun | verb prefix | full verb | translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| niin | nim- | nimbakade | I am hungry. |

| giin | gi- | gibakade | You are hungry. |

| wiin | —– | bakade | S/he is hungry. |

Here are two more examples. The dictionary forms for these verbs are maajaa and nibaa. Note that these are also the third-person singular forms (this only applies to VAI verbs – the other verb classes have their own dictionary forms, again the most minimal forms with no prefixes or suffixes).

| bare pronoun | full verb | translation |

|---|---|---|

| niin | nimaajaa | I leave |

| giin | gimaajaa | you leave |

| wiin | maajaa | s/he leaves |

| niin | ninibaa | I sleep |

| giin | ginibaa | you sleep |

| wiin | nibaa | s/he sleeps |

| niin | ningiishkaabaagwe | I am thirsty |

| giin | gigiishkaabaagwe | you are thirsty |

| wiin | giishkaabaagwe | s/he is thirsty |

Finally, the preverbs in this lesson. A preverb is a kind of prefix that comes before the main verb, modifying its meaning. Here we use wii-, which is a kind of future tense marker. OPD labels it as pv tns, a preverb of tense. You use this when indicating that someone will probably do something, that they want to do something or are volunteering to do it, like when you say “I’ll get it” when the house phone rings. It is less definite than the other future tense marker ga, which indicates more certainty that something will happen – as in giga-waabamin. The hyphen at the end of wii- reminds you that it comes before the verb, and it is common to use that hyphen in writing but not always. The preverb comes before the main verb, but after the prefix indicating person. So we have:

Grammatical rule: For VAI verbs ending in -o or -i, that final short vowel is deleted for the first-person niin and second-person singular giin forms, but it remains for third person wiin. We will illustrate this for two VAI verbs whose citation forms are the third person singular: wiisini and giigido. The first-person prefix for verbs starting in g is nin-. So we have:

Particles are little words that fulfill specific grammatical functions. Again, the OPD distinguishes many different kinds, and we will tell you the part of speech as listed in the OPD, but we will not delve deeply into the meaning of those categories. For now, we will discuss na and enya’, both of which are classified as pc disc, or discourse particles.

Na is an important word that marks yes/no questions. To turn a statement into a question, you simply add na as the second word of the sentence. It may also be ina, if following a hard pronounced consonant. So we have:

| Gibakade. | You are hungry. |

| Gibakade na? | Are you hungry? |

| Niwii-wiisin omaa. | I want to eat here. |

| Giwii-wiisin na omaa? | Do you want to eat here? |

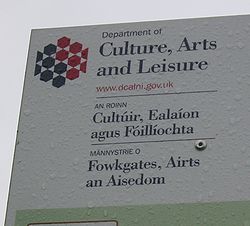

Am Learning about different Languages – including Gaelic Spelling – since it seems to be unknown and a bit Aracheaic – as it was repressed under the Crown for hundreds of years; @Language revival; similar history with native Languages in North America; like Ojbwe, cree and the Like – Kids used to be forbidden to speak their own language at school;

IRISH LANGUAGE OVERVIEW

The query “irish officially recognized language 19” does not correspond to a single factual event, but the year 1922 is significant as it was the year the first Irish Constitution was enacted, which established Irish as a “national language” and a “first official language”. This status was reaffirmed in the 1937 Constitution and has been maintained in the Republic of Ireland since.

KEY POINTS:

1922:The first Irish Constitution recognized the Irish language as the “national language” and a “first official language”.

Status:Irish remains the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland. English is recognized as the second official language.

Official Languages Act (2003):This legislation further solidified the status of the Irish language, requiring public bodies to provide services in Irish.

European Union:Irish was made an official language of the EU in 2007 and gained full working language status in 2022.

IRISH/ GAELIC – WIKEPEDIA ARTICLE

Irish (Standard Irish: Gaeilge), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic (/ˈɡeɪlɪk/ ⓘ GAY-lik),[4][5][4][6][7][8][9] is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family that belongs to the Goidelic languages and further to Insular Celtic, and is indigenous to the island of Ireland.[10] It was the majority of the population’s first language until the 19th century, when English gradually became dominant, particularly in the last decades of the century, in what is sometimes characterised as a result of linguistic imperialism. (wkepedia)

Written Irish is first attested in Ogham inscriptions from the 4th century AD,[25] a stage of the language known as Primitive Irish. These writings have been found throughout Ireland and the west coast of Great Britain.

Primitive Irish underwent a change into Old Irish through the 5th century. Old Irish, dating from the 6th century, used the Latin alphabet and is attested primarily in marginalia to Latin manuscripts. During this time, the Irish language absorbed some Latin words, some via Old Welsh, including ecclesiastical terms: examples are easpag (bishop) from episcopus, and Domhnach (Sunday, from dominica).

By the 10th century, Old Irish had evolved into Middle Irish, which was spoken throughout Ireland, the Isle of Man and parts of Scotland. It is the language of a large corpus of literature, including the Ulster Cycle. From the 12th century, Middle Irish began to evolve into modern Irish in Ireland, Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, and Manx on the Isle of Man.

Early Modern Irish, dating from the 13th century, was the basis of the literary language of both Ireland and Gaelic-speaking Scotland.

Modern Irish, sometimes called Late Modern Irish, as attested in the work of such writers as Geoffrey Keating, is said to date from the 17th century, and was the medium of popular literature from that time on.[26][27]

From the 18th century on, the language lost ground in the east of the country. The reasons behind this shift were complex but came down to a number of factors:

Main article: Irish language in Northern Ireland

Before the partition of Ireland in 1921, Irish was recognised as a school subject and as “Celtic” in some third level institutions. Between 1921 and 1972, government in Northern Ireland was devolved. During those years, the political party holding power in the Stormont Parliament, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), was hostile to the language as it was almost exclusively used by nationalists.[71] In broadcasting, reporting minority cultural issues was prohibited and Irish was excluded from radio and television for almost the first fifty years of the devolved government.[72]

After the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, Irish in Northern Ireland gradually gained a degree of formal recognition from the United Kingdom.[73] Then, in 2003, the British government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages with respect to the use of Irish in Northern Ireland. In the 2006 St Andrews Agreement, the British government promised to enact legislation to promote the language[74] and in 2022 it approved legislation to recognise Irish as an official language alongside English. The bill received royal assent on 6 December 2022.[2]

The status of Irish has often been used as a bargaining chip during government formation in Northern Ireland, prompting protests from organisations and groups such as An Dream Dearg.[75]

IRISH, LANGUAGE, HISTORY, REPRESSION, SOUNDS;

LANGUAGE REPRESSION IN EX SOVIET UNION – USSR

The USSR significantly repressed local languages through deliberate language policies that promoted Russification and Cyrillicization, especially in the late 1930s, to foster political unity and eliminate nationalist sentiments. Early efforts included shifting away from Arabic and Latin scripts to Cyrillic for Turkic and other languages, severing cultural ties and enhancing control. Later policies mandated Russian as a compulsory school subject, suppressed local media and publications, and purged non-Russian national elites accused of fostering division.

Early Soviet Period (Post-1917):

Russification in Education and Culture:

Long-Term Consequences:

Decline of Non-Russian Languages:The policies led to a decline in the use of many native languages, particularly among younger generations, and a widespread adoption of Russian as a second language.

SOVIET UNION – LANGUAGE SUPPRESSION

CANADA – INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES – SUPPRESSION – INDIAN ACT

Language repression in Canada involved colonial policies like the Indian Act and the residential school system, which forcibly prohibited Indigenous languages and punished children for speaking them, leading to widespread cultural loss and intergenerational trauma. This systemic suppression aimed to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society, resulting in the endangerment and potential extinction of many Indigenous languages today. Efforts to counter this legacy include the Indigenous Languages Act of 2019, funding for revitalization programs, and community-led initiatives to restore pride and pass languages to future generations.

The Historical Context of Language Repression

Residential Schools:A primary tool of assimilation was the residential school system, which removed Indigenous children from their families and communities.

Prohibition and Punishment:Students were forbidden to speak their mother tongues and faced severe punishment for doing so.

Cultural Genocide:This was a deliberate attempt to destroy Indigenous cultures by silencing their languages, which is a form of cultural genocide.

Indian Act:This legislation and associated colonial policies further reinforced the ban on Indigenous languages and traditions, contributing to their decline.

IMPACT OF LANGUAGE REPRESSION

Revitalization and Reclamation Efforts

REVITALIZATION AND RECLAMATION EFFORTS:

Indigenous Languages Act:In 2019, Canada passed the Indigenous Languages Act to support the preservation, revitalization, and strengthening of Indigenous languages.

Funding and Resources: Government funding and community-led initiatives provide resources for language programs, such as immersion schools, educational materials, and digital resources.

Community Involvement: Elders, language speakers, educators, and communities are actively working to revitalize languages through “language nests,” classrooms, and online platforms.

Promoting Pride and Healing: These efforts aim to restore cultural pride, rebuild self-esteem, and ease the intergenerational trauma caused by past policie

In the Irish language, instead of saying “I miss you” we say “braithim uaim thú” which literally means I feel you away from me. (eg. You took a part of Me – with your Leaving);

In the Irish language, instead of saying “I miss you” we say “braithim uaim thú” which literally means I feel you away from me.

This short phrase isn’t perfect Irish, but it builds on the idea of an Anam Cara, a “soul friend” and roughly translates as “My Soul Mate” or “My Soul Friend.”

The ancient Celts believed in a soul that radiated about the body. When two individuals formed a deep bond, they believed their souls would mingle and each person could be said to have found their Anam cara, or “soul friend.” It is this beautiful phrase that inspired our Mo Anam Cara jewelry and is a popular choice for engravings too!

2. A chuisle mo chroí (Ah Kooish-la mu kree) or Mo chuisle (Mu Kooish-la)

The literal translation of a chuisle mo chroí is “the pulse of my heart” or “my pulse.” This might be a little anatomical for some. But anyone who has felt their heart race at the sight of their loved one is sure to identify with the sentiment.

Translated as “shining” or “bright love of my heart” this is a beautiful phrase with a wonderful lightness that eloquently captures the wonderful warm feeling of being in love. Perhaps as a result, it pops up in several Irish love songs and ballads with records back to 1855.

“You are my love,” or is tú mo ghrá, is probably the closest we come to saying “I love you” in Irish.

Translated as “love forever” or ” forever love” this phrase emphasises eternity, an important theme in Celtic culture, represented by the unbroken form of Celtic and Trinity Knots.

Another phrase that might be a little anatomical for some, it roughly translates as “my heart is in you.” We see this phrase as going some way toward capturing the sense of the selflessness of love. It can be used for a romantic relationship but also works equally well used as a phrase for a parents love for a child.

This translates as “You are my (little) sweetheart”. The “-ín” at the end of Stóirín makes the word stór (sweetheart) diminutive. But rather than it being a cutesy ‘baby-speak’ it makes the term even more affectionate.

https://www.facebook.com/share/r/1CLSAceK2G/– with Staurt Mackey – In the Irish language, instead of saying “I miss you” we say “braithim uaim thú” which literally means I feel you away from me.

#Irish #language #Love #Phrases

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die — to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream — ay, there’s the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause — there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of dispriz’d love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovere’d country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.

#Qur’an for Kids; #Arabic language for Kids; #Kids Islamic Course; English for Beginners; #Nourani Qaeda (Arabic Alphabets and some Pronounciation); Qur’an for Adults, Kitab at Tawheed; #Tajweed;

info@elnouracademy.com; +13435538800 phone number Canada;