https://reedsy.com/resources/writing-apps/book/

Every writer needs a Studio

A place to plan, draft, edit, and typeset your book.

https://reedsy.com/studio – REEDSY STUDIO – Online Story and Notes Writing;

FocusWriter is a simple, distraction-free word processor. It utilizes a hide-away interface that you access by moving your mouse to the edges of the screen, allowing the program to have a familiar look and feel to it while still getting out of the way so that you can immerse yourself in your work.

FocusWriter allows you to customize your environment by creating themes that control the font, colors, and background image to add ambiance. It also features on-the-fly updating statistics, daily goals, multiple open documents, spell-checking, and much more.

Additionally, when you open the program your current work in progress will automatically load and position you where you last left off so that you can immediately jump back in.

SSuite WordGraph is a free and very useful alternative to Microsoft’s Word, OpenOffice’s Writer, or anything else out there claiming to be the latest and greatest. You don’t even have a need for .NET or even JAVA to be installed. This will save you a lot of hard drive space and precious computer resources.

Platforms: Windows, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Chrome, Android, PC

Best for: Drafting, Story, Book, Essay, and Free

Website: https://www.ssuiteoffice.com/software/wordgraph.htm

CAMPFIRE -ONLINE WRITING

https://www.campfirewriting.com

GOODNOTES

Capture every detail

Use the flexibility of voice, text, or Goodnotes’ renowned digital handwriting to capture any thought, in a digital notebook, Whiteboard, or a Text Document.

So, You’re looking to write a book. Well, wavemaker is here to help. It’s much much more than a text editor.

Platforms: Mac, Windows, Chrome, Android, Online, PC

Best for: Outlining, Drafting, Book, Story, and Free

Website: https://wavemaker.cards/

Base price: Free; Premium price: –

Connects to Google Docs;

Connects to Google Docs;  Mind maps

Mind maps  Timelines

Timelines

https://www.literatureandlatte.com

Scrivener is the go-to app for writers of all kinds, used every day by best-selling novelists, screenwriters, non-fiction writers, students, academics, lawyers, journalists, translators and more.

Platforms: Mac, Windows, iPhone, iPad, PC

Best for: Outlining, Drafting, Editing, Publishing, Book, and Story

Website: https://www.literatureandlatte.com/scrivener/overview ; Base price: $59.99 one-time payment

Premium price: –  Flexible corkboard

Flexible corkboard  Structure outliner

Structure outliner

Metadata and target setting

Metadata and target setting  Print and export functionalities

Print and export functionalities

Textilus Pro is a great word processor app for students and business people, also being excellent for writing reports, papers, blog posts, journals or ebooks! Textilus Pro can help you organize your research, generate ideas, and remove distractions so you can focus on the most important thing: writing. Platforms: Mac, iPhone, iPad

Best for: Note-taking, Drafting, Blog, Essay, and Free

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/word-processor-textilus-pro/id1018671847

What is yWriter?

yWriter is a powerful novel-writing program which is free to download and use. It’s designed for Windows 7 and later.yWriter is a word processor which breaks your novel into chapters and scenes, helping you keep track of your work while leaving your mind free to create. It will not write your novel for you, suggest plot ideas or perform creative tasks of any kind. yWriter was designed by an author, not a salesman!

yWriter7 is free to download and use, but you’re encouraged to register your copy if you find it useful.

If you’re just embarking on your first novel a program like yWriter may seem like overkill. I mean, all you have to do is type everything into a word processor! Sure, but wait until you hit 20,000 words, with missing scenes and chapters, notes all over your desk, characters and locations and plot points you’ve just added and which need to be referenced earlier … it becomes a real struggle. Now imagine that same novel at 40,000 or 80,000 words! No wonder most first-time writers give up.

https://www.spacejock.com/yWriter7_Download.html

Mellel is a word processor designed from the ground up to be the ultimate writing tool for academics, technical writers, scholars and students. Mellel is strong, stable and reliable, and is the ideal companion for working on documents that are long and complex, short and simple, or anything in between.

Platforms: Mac, iPhone, iPad Best for: Outlining, Drafting, and Essay

Website: https://mellel.com/

Base price: $49.00 one-time payment

Outline

Outline  Bibliography

Bibliography  Footnotes and endnotes

Footnotes and endnotes

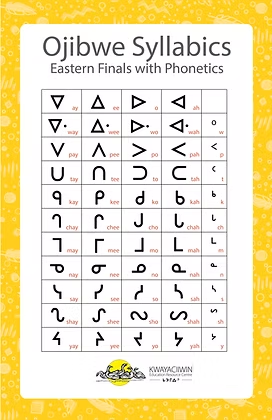

Multilingual support

Multilingual support

Pages is a powerful word processor that lets you create stunning documents, and comes included with most Apple devices. And with real-time collaboration, your team can work together from anywhere, whether they’re on Mac, iPad, iPhone, or a PC.

Platforms: iPad, Mac, iPhone

Best for: Drafting, Book, Essay, Journal, Poetry, Story, Blog, and Free

Website: https://www.apple.com/pages/

Base price: Free

Full feature word processor

Full feature word processor  Track changes

Track changes

Syncs across devices

Syncs across devices  Offline collaboration

Offline collaboration

https://bear.app

Seamless Markdown – Bear App

- Work your way with text, photos, tables, and todo lists, all in the same note

- Easily organize notes and projects with flexible tags

- Format notes with simple Markdown that adapts to any situation

LibreOffice is a free and powerful office suite, and a successor to OpenOffice.org (commonly known as OpenOffice). Its clean interface and feature-rich tools help you unleash your creativity and enhance your productivity.

Platforms: Mac, Windows, PC

Best for: Drafting, Book, Essay, Journal, Poetry, Story, Blog, and Free

Website: https://www.libreoffice.org/ – Base price: Free

Full-feature word processor

Full-feature word processor  Customizable fonts and other styles

Customizable fonts and other styles

*Lists for Writers

Are you stuck in a rut? Do you have writer’s block? Need a quick plot idea for that short story writing assignment that’s due tomorrow? Lists for Writers is here to help!

What is it? Lists for Writers is exactly that – lists for writers. We’ve compiled a variety of lists to help writers, both young and old, come up with brainstorming ideas.

Lists for Writers is a great addition to any writer’s toolbox. Helpful to both novice and expert writers alike, this app delivers list after list of prompts and ideas for your brainstorming sessions: names, character traits, plot lines, occupations, obsessions, action verbs, and much more! Whether you are working on a creative writing project, a short story, an essay assignment, National Novel Writing Month / NaNoWriMo, or your next fiction book, this app helps get it done.

It is available now in the iTunes App Store and is a universal app that works for iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. It is also available for Android in the Google Play Android market, for Android and Kindle Fire in the Amazon Appstore for Android, for NOOK in the NOOK store, for Windows Phone in the Windows Phone Store, and for BlackBerry 10 in BlackBerry World.

Website: https://thinkamingo.com/lists-for-writers/

Simple Note:

https://simplenote.com

The simplest way to keep notes

All your notes, synced on all your devices. Get Simplenote now for iOS, Android, Mac, Windows, Linux, or in your browser.

ApolloPad is a feature-packed online writing environment that will help you finish your novels, ebooks and short stories.

Platforms: Online

Best for: Outlining, Drafting, Story, Book, and Free

Website: https://apollopad.com/ -Base price: Free

Project outlining & timelines

Project outlining & timelines  Notes in context

Notes in context  To-do lists

To-do lists

https://thequill.app – The Quill App

WPS Office is a lightweight, feature-rich comprehensive office suite with high compatibility. As a handy and professional office software, WPS Office allows you to edit files in Writer, Presentation, Spreadsheet, and PDF to improve your work efficiency.

Platforms: Mac, Windows, Android, iPad, iPhone, PC

Best for: Drafting, Book, Essay, Journal, Poetry, Story, Blog, and Free

Website: https://www.wps.com/

Base price: Free Premium price: $29.99 monthly

Cross platform file management

Cross platform file management  Free templates

Free templates  Colorful themes

Colorful themes

Still looking for the perfect app to write your novel? Novelist might just be the perfect tool for the job!

Platforms: Android, iPhone, iPad, Online

Best for: Outlining, Worldbuilding, Drafting, Story, Book, and Free

Website: https://www.novelist.app/ -Base price: Free

Goal setting

Goal setting  Rich text editor

Rich text editor  Back up and restore

Back up and restore

SQUIBLER

https://www.squibler.io

Turn Your Idea into a Story

Write books, novels, and screenplays by chatting with AI. Say goodbye to writer’s block.

A real-time rhyme suggestion engine offering color-coded rhyme highlighting, the ability to save your work to the cloud, the power to embed SoundCloud jams into your notes, customizable visual layouts, and more.

Platforms: Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android

Best for: Drafting, Poetry, and Free

Website: https://www.rhymersblock.com/welcome

Base price: Free

Real-time ryhme suggestions

Real-time ryhme suggestions  Slant/near ryhme suggestions

Slant/near ryhme suggestions

Word frequency analysis

Word frequency analysis  Color-coded ryhmes

Color-coded ryhmes

Create documents, make impact. When your work needs to wow, Craft gives you the tools to make it magnificent.

Platforms: Mac, iPhone, iPad, Windows, Online, PC

Best for: Note-taking, Drafting, Journal, Essay, Blog, and Free

Website: https://www.craft.do/

Base price: Free; Premium price: $5.00 monthly

AI writing assistant

AI writing assistant  Document structuring

Document structuring

Customizable

Customizable  Collaboration

Collaboration